Abstract

Background:

A pre-colonoscopy consultation in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening is necessary to assess a screenee’s general health status and to explain benefits and risks of screening. The first option allows for personal attention, whereas a telephone consultation does not require travelling. We hypothesised that a telephone consultation would lead to higher response and participation in CRC screening compared with a face-to-face consultation.

Methods:

A total of 6600 persons (50–75 years) were 1 : 1 randomised for primary colonoscopy screening with a pre-colonoscopy consultation either face-to-face or by telephone. In both arms, we counted the number of invitees who attended a pre-colonoscopy consultation (response) and the number of those who subsequently attended colonoscopy (participation), relative to the number invited for screening. A questionnaire regarding satisfaction with the consultation and expected burden of the colonoscopy (scored on five-point rating scales) was sent to invitees. Besides, a questionnaire to assess the perceived burden of colonoscopy was sent to participants, 14 days after the procedure.

Results:

In all, 3302 invitees were allocated to the telephone group and 3298 to the face-to-face group, of which 794 (24%) attended a telephone consultation and 822 (25%) a face-to-face consultation (P=0.41). Subsequently, 674 (20%) participants in the telephone group and 752 (23%) in the face-to-face group attended colonoscopy (P=0.018). Invitees and responders in the telephone group expected the bowel preparation to be more painful than those in the face-to-face group while perceived burden scores for the full screening procedure were comparable. More subjects in the face-to-face group than in the telephone group were satisfied by the consultation in general: (99.8% vs 98.5%, P=0.014).

Conclusion:

Using a telephone rather than a face-to-face consultation in a population-based CRC colonoscopy screening programme leads to similar response rates but significantly lower colonoscopy participation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Screening programs for colorectal cancer (CRC) are being implemented in most Western countries. In 2009, 19 out of 27 European countries had established or were preparing a population-based or opportunistic CRC screening programme (Zavoral et al, 2009). Although screening for CRC is gaining acceptance throughout the world, a consensus on the preferred strategy is still lacking. Colonoscopy is a colorectal exam with a high accuracy to detect colorectal neoplasia and one of the recommended screening strategies by the US Taskforce (Levin et al, 2008). Colonoscopy is, however, a burdensome procedure that requires complete colon lavage. For a primary screening test, it has a relatively high complication rate of 0.1–0.3% (Nelson et al, 2002; Panteris et al, 2009). When colonoscopy is used as a primary screening method, the risks and benefits of screening therefore have to be explained to participants before screening to enable informed decision making. Besides, information on a person’s medical history and medication use should be obtained to anticipate on possible risks during colonoscopy. On one hand screenees need to be adequately informed on the risks and benefits of the procedure, and on the other hand the endoscopist and screening organisation require adequate information on the health status of the individual screenee and the need for any specific precautions. Both aims can be achieved in a pre-colonoscopy consultation.

Most hospitals in the Netherlands invite patients at the outpatient clinic prior to colonoscopy. Although this is working well in daily clinical practice, it may overload the outpatient clinic when used in screening.

An alternative for a face-to-face consultation could be a telephone consultation. Travelling to and from the hospital with absence from home or work would no longer be necessary, which could facilitate participation. On the other hand, bowel preparation may be less well explained during telephone conversations, which would lead to lower quality exams. Telephone conversations may provide less room for additional questions, leading to lower satisfaction levels and inferior participation rates. Furthermore, participants’ expected burden of the colonoscopy might be influenced by the type of assessment.

The primary aim of this randomised trial was to compare the response rate and participation rate with pre-colonoscopy assessment by telephone to that of a face-to-face consultation at the outpatient clinic. Secondary outcomes were participants’ satisfaction, expected and perceived burden and quality of bowel preparation. Our a priori hypothesis was that more invitees would have a pre-colonoscopy assessment in the telephone group than in the face-to-face group, because these invitees could stay at home or at work during the consultation. We expected that a higher response rate in the telephone group would lead to a higher colonoscopy participation rate, because these invitees would have to come to the hospital only once. We also expected participants in the face-to-face group to be more satisfied with the consultation and that the quality of bowel preparation would be higher in this group. We anticipated no difference between both groups regarding expected burden and perceived burden of the colonoscopy.

Materials and methods

Randomisation and invitation

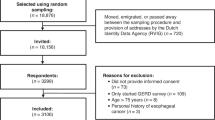

A group of 6600 persons aged 50–75 years of the general Dutch population in the regions Amsterdam and Rotterdam was randomly allocated, prior to invitation, to either a face-to-face pre-colonoscopy consultation (n=3298) or a telephone consultation (n=3302) (Figure 1). Individuals were identified using the electronic databases of the regional municipal administration registration. Randomisation was performed per household. The randomisation was performed by TENALEA, using ALEA Randomisation software (version 2.2) (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), based on a minimisation algorithm taking into account age (50–55, 55–60, 60–65, 65–70 and 70–75), gender and socio-economic status (very low, low, average, high and very high). At the time of the trial, the Netherlands did not have a CRC screening programme.

Study flow: response, participation and questionnaire completion. *Only a subsequent subset of 5924 invitees received the baseline questionnaire. The participants who belonged to this subset received the PBQ. The proportions of completed EBQ, SQ or PBQ are relative to this subset. **Non-participant who attended the consultation. ***Subjects with CRC-related symptoms. Abbreviations: EBQ=expected burden questionnaire; GP=general practitioner; PBQ=perceived burden questionnaire; SQ=satisfaction questionnaire.

All individuals were invited between June 2009 and July 2010 by the Regional Comprehensive Centres in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. They received a pre-announcement, followed by an invitation and an information leaflet, containing information on CRC in general, the advantages and disadvantages of screening, possible risks and follow-up in case of a positive test result. If invitees failed to respond, they were sent a reminder letter 4 weeks later for the same assessment type as in the first invitation (de Wijkerslooth et al, 2010). The overall design of the COCOS (COlonoscopy or COlonography for Screening) trial has been described in detail previously (de Wijkerslooth et al, 2010). The primary outcomes of the COCOS trial (participation rate and diagnostic yield) were published recently (Stoop et al, 2012). Ethical approval was obtained from the Dutch Health Council (2009/03WBO, The Hague, The Netherlands). The trial was included in the Dutch trial register prior to its initiation: NTR1829 (www.trialregister.nl).

Pre-colonoscopy assessment

At two academic centres in the Netherlands, face-to-face and telephone pre-colonoscopy consultations were performed by clinical research staff. A formalized consultation was performed with standardized questions (Table 1) using a shared database in both hospitals. For both consultation types, 30 min were scheduled. During the consultation, possible screening exclusion criteria were discussed. Persons were excluded when they had had a full colonic exam (colonoscopy, double contrast barium enema or CT colonography) in the previous 5 years or when they were in a surveillance programme because of a personal history of CRC, colonic adenomas or inflammatory bowel disease. Persons with an end-stage disease and a life expectancy <5 years were also excluded.

If additional information was needed on possible exclusion criteria or contraindications for the screening procedure, the general practitioner or medical specialist was contacted for further information. In the telephone group, respondents were invited at the outpatient clinic if the research staff felt that the telephone consultation had been inadequate.

During the second part of the consultation, information was given regarding the colonoscopy itself. Duration, discomfort and possible complications, such as bleeding or perforation (0.1–0.3%), were discussed. The research staff explained about the possibility of using conscious sedation (midazolam) and/or analgesics (fentanyl) during the procedure.

Invitees received detailed information about the bowel preparation during the consultation. In addition, they were handed bowel preparation materials. In the telephone group, this was distributed by mail. At the end of the consultation, information was given on how test results would be reported and corresponding follow-up measures. Informed consent was discussed during the assessment and, subsequently, an informed consent form was sent by postal mail to potential participants together with an information leaflet for reference. Participants were asked to return the informed consent form by mail before the scheduled colonoscopy.

At the end of the consultation, an appointment was made for the actual colonoscopy. All individuals who agreed to participate were sent a confirmation of the appointment for colonoscopy.

Baseline questionnaire

The first 5924 invitees received a validated baseline questionnaire by postal mail. Respondents to the first screening invitation received the questionnaire after the prior consultation, within 4 weeks before the scheduled colonoscopy. Invitees who had not responded to the initial invitation received the same baseline questionnaire 4 weeks after the initial invitation, together with the reminder. All individuals were asked to complete the questionnaire and to return it by mail in a pre-paid envelope.

The baseline questionnaire comprised items regarding satisfaction with the prior consultation (SQ) and expected burden (EBQ) of the colonoscopy (Table 2). Items on satisfaction were based on a previously validated questionnaire on satisfaction in eight university hospitals in The Netherlands (Prismant: Trends in tevredenheid, 2008). Satisfaction was scored on a four-point scale ranging from very satisfied to very unsatisfied. Expected burden was itemised into expected embarrassment, pain and burden of the bowel preparation and the colonoscopy itself and was previously validated (van Gelder et al, 2004; Denters et al, 2009; Hol et al, 2010). The EBQ burden items such as embarrassment, pain and burden during the procedure were scored on five-point rating scales labelled as not embarrassing, painful or burdensome, to extremely embarrassing, painful or burdensome (1=not at all; 2=slightly; 3= somewhat; 4=rather; and 5=extremely). The questionnaire also collected information on background characteristics, such as educational and income levels. Completed baseline questionnaires were scanned and responses were automatically transferred to a database.

Perceived burden questionnaire (PBQ)

A PBQ was sent to screening participants, 2 weeks after the colonoscopy (Figure 1). Participants received this questionnaire together with their final test results. Participants were asked to fill in the PBQ questionnaire directly after receiving it and to return by mail in a pre-paid envelope. If participants did not respond, they were not reminded. This questionnaire had also been previously validated (van Gelder et al, 2004; Deutekom et al, 2006; Denters et al, 2009; Hol et al, 2010). It comprised colonoscopy-related items as well as items on the full procedure (including bowel preparation, colonoscopy itself, post-procedure follow-up and waiting for the test results). The perceived burden questions are listed in Table 3. All burden items were scored on a five-point rating scale ranging from not embarrassing, painful or burdensome to extremely embarrassing, painful or burdensome (1=not at all; 2=slightly; 3= somewhat; 4=rather; and 5=extremely). Participants were also asked about their willingness to participate in a future screening round (1=absolutely not; 2=probably not; 3=probably; and 4=certainly). Completed PBQs questionnaires were scanned and responses were automatically transferred to a database.

Colonoscopy

All colonoscopies were performed by experienced gastroenterologists (⩾1000 colonoscopies) according to the standard quality recommendations of the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (Rex et al, 2006). Conscious sedation (midazolam) and analgesics (fentanyl) were administered intravenously at the discretion of the participant and the endoscopist. Withdrawal time was at least 6 min. For bowel preparation, 2 l of polyethylene electrolyte glycol solution (Moviprep; Norgine BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) together with 2 l transparent fluid and a low-fibre diet for 2 days were used. Bowel preparation was scored using the validated Ottawa bowel preparation score (Rostom and Jolicoeur, 2004) and classified as excellent (0–3), good (4–6), sufficient (7–10) or inadequate (11–14). In case of inadequate bowel preparation, the colonoscopy was interrupted and re-scheduled, unless the participant refused to undergo re-colonoscopy.

Data analysis

The analysis was based on the intention-to-screen principle. The primary outcome measures were the response rate, defined as the number of invitees attending the pre-colonoscopy consultation relative to the total number of invitees, and the participation rate, defined as the number of invitees who underwent a colonoscopy relative to the total number of invitees. Differences in response and participation rates between groups were evaluated using Chi-square test statistics. Results were not adjusted for clustering, as in most instances there were only one or two eligible subjects per household. Items on satisfaction of the consultation and expected and perceived burden of the colonoscopy were expressed as mean scores and compared using Mann–Whitney U-test. Expected burden was compared for all invitees, responders (invitees who attended the consultation) and non-participants (responders who did not attend the colonoscopy). In the analysis of the expected burden and satisfaction scores for responders, questionnaires were excluded if completed before the consultation. All the baseline questionnaires that had not been completed before the colonoscopy were excluded from the analysis. Quality of bowel preparation was expressed as percentages per category and compared using Chi-square statistics. The software programme SPSS for Windows, version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all of the analyses.

Sample size

We expected an overall participation rate of 25% in colonoscopy screening. We anticipated a participation rate of 22.5% in the face-to-face group vs 27.5% in the telephone consultation group. Including 5000 invitees in this trial would result in a power of 98% to reject the null hypothesis of no difference, using two degrees of freedom Chi-square test with a significance level set at 0.05.

Results

Response and participation

Figure 1 summarises the study flow. In the telephone group, 794 of the 3302 invitees (24%) attended the pre-colonoscopy consultation vs 822 of the 3298 invitees (25%) in the face-to-face group. This difference in response rate was not significant (P=0.41). (Figure 1) One responder in the telephone group was invited at the outpatient clinic because of severe comorbidity and was subsequently excluded from colonoscopy.

In total, 18 participants in the telephone group and 14 in the face-to-face group were excluded after the pre-colonoscopy assessment because they met one or more exclusion criteria. After the pre-colonoscopy consultation, 102 responders in the telephone group and 65 in the face-to-face group decided not to undergo a colonoscopy. The participation rate was significantly lower in the telephone group: 674 invitees (20%) had a screening colonoscopy after the telephone consultation vs 752 (23%) in the face-to-face group (P=0.018). Demographic characteristics of responders and participants are listed in Table 4.

Baseline questionnaire

Expected burden among all invitees

We had to exclude 27 questionnaires that were returned after the colonoscopy. Questions on expected burden were completed by 1083 of 2958 individuals (37%) invited for a face-to-face consultation and by 1001 of 2966 individuals (34%) invited for a telephone consultation.

Figure 2 summarises the expected burden scores of all invitees. Reluctance to undergo screening was comparable in both groups. The expected embarrassment and burden of the bowel preparation was scored comparable in both groups. A larger proportion of invitees allocated to the telephone consultation expected the bowel preparation to be somewhat painful: 26% vs 22%, with an overall mean score of 2.4 vs 2.3 (P=0.03). Mean scores for expected embarrassment, pain and burden of the colonoscopy itself were not statistically different between the two groups.

Reluctance to undergo colonoscopy and expected embarrasement, pain and burden of bowel prep and colonoscopy. On top of the bars, mean score, s.d. (between parantheses), difference in mean scores and pooled s.d. (pSD) are displayed. Expected pain of the bowel preparation differed significantly between the groups (P=0.03), all other items were not statistically different.

Expected burden among responders (invitees who attended the consultation)

Items on expected burden were completed by 578 of the 736 responders (79%) who attended a face-to-face consultation and by 524 of the 701 responders (75%) with a telephone consultation. Mean expected embarrassment and burden scores of the bowel preparation were similar for the two groups; the expected pain of the bowel preparation was rated higher in the telephone group: 20% in the telephone group expected it to be rather painful vs 16% in the face-to-face group; overall mean scores were 2.1 vs 2.0 (P=0.03). Expected embarrassment, pain and burden of the colonoscopy itself were similar for both groups.

Expected burden in non-participants who did attend the consultation

In the telephone group, 33 of the 102 non-participants (32%) completed the questions on expected burden vs 24 of the 56 (43%) in the face-to-face group. Scores on expected embarrassment, pain and burden of the bowel preparation and the colonoscopy itself did not significantly differ between the groups.

Satisfaction among responders

A total of 585 of the 736 responders (79%) in the face-to-face group completed the items on satisfaction after the consultation, vs 472 of the 701 responders (67%) in the telephone group. Table 5 summarises the level of satisfaction during the consultation for both groups.

Almost all responders in the face-to-face group and in the telephone group indicated to be (very) satisfied with the assessment in general (99.8% vs 98.5%, P=0.014). Responders reported to be (very) satisfied with the personal attention from the research staff: 98.9% in the telephone group vs 100% in the face-to-face group (P=0.011). The clarity of the information given during the assessment was scored as (very) satisfying by 98.5% in the telephone group vs 99.5% in the face-to-face group (P=0.10). All responders (100%) in the face-to-face group expressed being satisfied with the possibility to ask questions vs 99.1% in the telephone group (P=0.023).

Bowel preparation

Four colonoscopies in the telephone group and three in the face-to-face group had to be re-scheduled because of an inadequate bowel preparation. Mean Ottawa scores for the quality of the bowel preparation in participants were similar: 5.7 in the telephone group vs 5.6 in the face-to-face group (P=0.54) (Table 6).

The perceived burden

In the telephone group, 574 (85%) colonoscopies were performed under conscious sedation in combination with analgesics compared with 647 (86%) colonoscopies in the face-to-face group. (P=0.40). The PBQ was completed by 477 of 674 (71%) participants with a telephone consultation and 529 of 752 (70%) participants with a face-to-face consultation. Scores on perceived embarrassment, pain and burden of the full screening procedure were similar in both groups (Figure 3). In participants, 95.5% in the telephone group and 96.2% in the face-to-face group would (probably) participate in a future screening round (P=0.58).

Perceived embarrasement, pain and burden of the entire screening procedure (including bowel preparation colonoscopy itself, waiting for the test results, and abdominal complaints). On top of the bars, mean score, s.d. (between parantheses), difference in mean scores and pSD are displayed. None of the items were statistically different between the groups: pain (P=0.06), embarrassement (P=0.96) and burden (P=0.75).

Discussion

We compared pre-colonoscopy consultation by telephone with face-to-face assessment in a population-based CRC screening programme in average-risk subjects. The response rate was similar for telephone and face-to-face assessments, with about 25% of the invitees having the assessment. Colonoscopy participation on the other hand was significantly higher among individuals in the face-to-face group. Satisfaction was marginally, but significantly, lower and expected burden scores higher after telephone assessment.

Our study has several strengths. All invitees in this randomised controlled trial were screening naive subjects and were randomly selected prior to the invitation to one of the two consultation types. Invitees received an invitation for only one of the two consultation types in combination with an identically designed detailed information leaflet. In this way, information supply and decision making was kept as simple and clear as possible. Information provided during the consultation was kept similar; a standardised questionnaire was used to keep the two assessment types comparable. In each centre, the same research staff performed both types of assessments, minimising bias in the comparison. Nevertheless, differences may have occurred in the information exchanged with invitees. At the outpatient clinic, information supply can be simplified and made clearer using visual aids, for example.

In our study, 20% of the invitees in the telephone group participated in screening and 23% in the face-to-face group. This compares well with the attendance rates in other colonoscopy screening programs. The participation rate in colonoscopy population screening in Australia was 16% (Scott et al, 2004). Two Italian randomized controlled trials, in which invitees were selected by general practitioners, reported primary colonoscopy participation rates of 10 and 27% (Segnan et al, 2007; Lisi et al, 2010). The annual participation rates for the age group 55–69 years in the opportunistic colonoscopy screening programme in Germany are 3% for men and 4% for women (Brenner et al, 2009).

To our knowledge, only one previous, non-randomised study compared a face-to-face pre-colonoscopy assessment with a telephone assessment in CRC screening using gFOBT as the primary screening method (Rodger and Steele, 2008). This retrospective study, performed in Scotland, compared participation, satisfaction of the participant, and quality of bowel preparation in 316 gFOBT-positive participants in the first year of screening (with a face-to-face consultation) with 388 gFOBT-positive participants in the second year of screening (with a choice for face-to-face or telephone consultation). Overall, colonoscopy attendance was significantly higher in the second year: 99% vs 85%. These results are difficult to compare with ours, because of the non-randomized nature of the study and the optional choice for a face-to-face interview in the second year. Both in the Scottish study and in our study, quality of bowel preparation did not differ between the two groups.

Prior to colonoscopy, accurate information on bowel preparation must be provided to perform a high-quality exam. Inadequate bowel preparation can result in missed lesions, cancelled procedures, increased procedural time and a potential increase in complication rates. Adherence to instructions for preparation can be achieved by an accurate explanation prior to colonoscopy. Characteristics like age, gender, weight and comorbidity must be obtained before colonoscopy, because these may influence the quality of bowel preparation (Chung et al, 2009). Here also, in screening participants, we found no significant differences between both groups. This indicates that a telephone interview can be an adequate mode for preparing participants for colonoscopy.

In our study, we found significant differences in satisfaction between groups. It is conceivable that when participants feel satisfied with the personal attention and the opportunity to ask questions, they will be more compliant with screening. One may assume that a high level of satisfaction strengthens continuity of the participant–physician relationship (Ware and Hays, 1988; Haddad et al, 2000). Several previous studies have evaluated satisfaction regarding the colonoscopy (Lin et al, 2007; Chartier et al, 2009; Ko et al, 2009). In concordance with our results, usually very high satisfaction rates are found (Rosenthal and Shannon, 1997).

Expected burden may also influence participation in CRC screening. If invitees expect the colonoscopy to be highly burdensome, they can decide, before or after the pre-colonoscopy assessment, not to undergo colonoscopy (Multicentre Australian Colorectal-neoplasia Screening (MACS) Group, 2006; Ko et al, 2009). Expected burden can be influenced by the way the information is provided during the pre-colonoscopy assessment. In our study, significantly more invitees and responders in the telephone group expected the bowel preparation to be painful than in the face-to-face group. Not only expected burden but also perceived burden of colonoscopy influences the participation rate in future screening rounds. In our study, perceived burden was comparable between both groups, as well as the willingness to participate in a future screening round (96%). This suggests that the mode of pre-colonoscopy assessment does not affect the experience of actual screening participants.

Actual differences in satisfaction and expected burden scores between both groups were small, which makes the clinical relevance arguable. In a review published in 2003, the minimally important difference for health-related quality of life instruments was computed. In this review, the authors concluded that, to indicate clinical relevance, a difference of at least half a s.d. is needed (Norman et al, 2003). However, CRC screening by definition has to deal with large populations, and the impact of screening fully relies on consistent participation during repeated screening rounds. As such, small differences become relevant.

It is possible that other factors, besides expected burden and satisfaction with the assessment, caused invitees in the telephone group to refrain more often from actual participation. Unfortunately, a considerable proportion of responders who did not attend colonoscopy failed to report the reason for not participating. Maybe the way in which the contact is initiated affects the developing physician–patient relationship. We know from other studies that this relationship can be influenced by the way participants are approached (Ha and Longnecker, 2010; Moretti et al, 2012). Non-verbal communication between a doctor and a patient affects patient’s satisfaction. Behaviour such as sitting close to the patient and leaning forward have been associated with higher patient satisfaction (Roter et al, 2006; Pawlikowska et al, 2012). A Dutch study reported on end points in medical communication to improve physician–patient communication (de Haes and Bensing, 2009). The authors suggested that one of the ways to check if a good physician–patient relationship is being established is to have eye contact with the patient, something which is obviously not possible during a telephone conversation. Having eye contact also enables the physician to check whether information given during the assessment is understood.

Although, response rates in both groups were similar, the telephone group had a higher post-consultation drop-out rate, or in other words a lower post-consultation uptake of colonoscopy, which is of key importance for the impact of CRC screening. The uptake rate of colonoscopy using a telephone consultation needs to be improved. Therefore, further research should focus on how to raise colonoscopy participation rate after a telephone consultation. Maybe an interactive conversation using a computer or information about the screening colonoscopy on video might increase commitment. Besides, information supply could be done using internet or email.

There may be alternatives to the face-to-face assessment as done in this study to evaluate and inform potential screening participants. One example is the additional use of a pre-assessment questionnaire. Future research should investigate the safety and preference of additional measures for improving pre-colonoscopy assessment in colonoscopy screening.

In summary, we found that a similar number of invitees responded to an invitation for a telephone consultation and to an invitation for a face-face consultation in a population-based CRC screening programme using colonoscopy as the primary screening method. The number of invitees who decided not to participate was significantly higher after the telephone assessment, whereas satisfaction was lower and expected burden higher. We therefore do not recommend switching to telephone consultation in primary colonoscopy screening programmes for CRC.

Change history

10 September 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Brenner G, Altenhofen L, Haug U (2009) Expected reduction of colorectal cancer incidence within 8 years after introduction of the German screening colonoscopy programme: estimates based on 1 875 708 screening colonoscopies. Eur J Cancer 45: 2027–2033

Chartier L, Arthurs E, Sewitch MJ (2009) Patient satisfaction with colonoscopy: a literature review and pilot study. Can J Gastroenterol 23: 203–209

Chung YW, Han DS, Park KH, Kim KO, Park CH, Hahn T, Yoo KS, Park SH, Kim JH, Park CK (2009) Patient factors predictive of inadequate bowel preparation using polyethylene glycol: a prospective study in Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol 43: 448–452

de Haes H, Bensing J (2009) Endpoints in medical communication research, proposing a framework of functions and outcomes. Patient Educ Couns 74: 287–294

de Wijkerslooth TR, de Haan MC, Stoop EM, Deutekom M, Fockens P, Bossuyt PM, Thomeer M, van Ballegooijen M, Essink-Bot ML, van Leerdam ME, Kuipers EJ, Dekker E, Stoker J (2010) Study protocol: population screening for colorectal cancer by colonoscopy or CT colonography: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol 10: 47

Denters MJ, Deutekom M, Fockens P, Bossuyt PM, Dekker E (2009) Implementation of population screening for colorectal cancer by repeated fecal occult blood test in the Netherlands. BMC Gastroenterol 9: 28

Deutekom M, Terra MP, Dijkgraaf MG, Dobben AC, Stoker J, Boeckxstaens GE, Bossuyt PM (2006) Patients’ perception of tests in the assessment of faecal incontinence. Br J Radiol 79: 94–100

Ha JF, Longnecker N (2010) Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J 10: 38–43

Haddad S, Potvin L, Roberge D, Pineault R, Remondin M (2000) Patient perception of quality following a visit to a doctor in a primary care unit. Fam Pract 17: 21–29

Hol L, de Jonge V, van Leerdam ME, van Ballegooijen M, Looman CW, van Vuuren AJ, Reijerink JC, Habbema JD, Essink-Bot ML, Kuipers EJ (2010) Screening for colorectal cancer: comparison of perceived test burden of guaiac-based faecal occult blood test, faecal immunochemical test and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Eur J Cancer 46: 2059–2066

Ko HH, Zhang H, Telford JJ, Enns R (2009) Factors influencing patient satisfaction when undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 69: 883–891

Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Johnson D, Johnson CD, Levin TR, Pickhardt PJ, Rex DK, Smith RA, Thorson A, Winawer SJ (2008) Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology 134: 1570–1595

Lin OS, Schembre DB, Ayub K, Gluck M, McCormick SE, Patterson DJ, Cantone N, Soon MS, Kozarek RA (2007) Patient satisfaction scores for endoscopic procedures: impact of a survey-collection method. Gastrointest Endosc 65: 775–781

Lisi D, Hassan CC, Crespi M (2010) Participation in colorectal cancer screening with FOBT and colonoscopy: an Italian, multicentre, randomized population study. Dig Liver Dis 42: 371–376

Moretti F, Fletcher I, Mazzi MA, Deveugele M, Rimondini M, Geurts C, Zimmermann C, Bensing J (2012) GULiVER--travelling into the heart of good doctor-patient communication from a patient perspective: study protocol of an international multicentre study. Eur J Public Health 22: 464–469

Multicentre Australian Colorectal-neoplasia Screening (MACS) Group (2006) A comparison of colorectal neoplasia screening tests: a multicentre community-based study of the impact of consumer choice. Med J Aust 184: 546–550

Nelson DB, McQuaid KR, Bond JH, Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Johnston TK (2002) Procedural success and complications of large-scale screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 55: 307–314

Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW (2003) Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 41: 582–592

Panteris V, Haringsma J, Kuipers EJ (2009) Colonoscopy perforation rate, mechanisms and outcome: from diagnostic to therapeutic colonoscopy. Endoscopy 41: 941–951

Pawlikowska T, Zhang W, Griffiths F, van Dalen J, van der Vleuten C (2012) Verbal and non-verbal behavior of doctors and patients in primary care consultations - How this relates to patient enablement. Patient Educ Couns 86: 70–76

Prismant: Trends in tevredenheid. d.t.v.p.v. & (2008) d.a.U.M.C.N.r

Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT, Safdi MA, Faigel DO, Pike IM (2006) Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 101: 873–885

Rodger J, Steele RJ (2008) Telephone assessment increases uptake of colonoscopy in a FOBT colorectal cancer-screening programme. J Med Screen 15: 105–107

Rosenthal GE, Shannon SE (1997) The use of patient perceptions in the evaluation of health-care delivery systems. Med Care 35: NS58–NS68

Rostom A, Jolicoeur E (2004) Validation of a new scale for the assessment of bowel preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc 59: 482–486

Roter DL, Frankel RM, Hall JA, Sluyter D (2006) The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits. Mechanisms and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 21 (Suppl 1): S28–S34

Scott RG, Edwards JT, Fritschi L, Foster NM, Mendelson RM, Forbes GM (2004) Community-based screening by colonoscopy or computed tomographic colonography in asymptomatic average-risk subjects. Am J Gastroenterol 99: 1145–1151

Segnan N, Senore C, Andreoni B, Azzoni A, Bisanti L, Cardelli A, Castiglione G, Crosta C, Ederle A, Fantin A, Ferrari A, Fracchia M, Ferrero F, Gasperoni S, Recchia S, Risio M, Rubeca T, Saracco G, Zappa M (2007) Comparing attendance and detection rate of colonoscopy with sigmoidoscopy and FIT for colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology 132: 2304–2312

Stoop EM, de Haan MC, de Wijkerslooth TR, Bossuyt PM, van Ballegooijen M, Nio CY, van de Vijver MJ, Biermann K, Thomeer M, van Leerdam ME, Fockens P, Stoker J, Kuipers EJ, Dekker E (2012) Participation and yield of colonoscopy versus non-cathartic CT colonography in population-based screening for colorectal cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 13: 55–64

van Gelder RE, Birnie E, Florie J, Schutter MP, Bartelsman JF, Snel P, Lameris JS, Bonsel GJ, Stoker J (2004) CT colonography and colonoscopy: assessment of patient preference in a 5-week follow-up study. Radiology 233: 328–337

Ware JE, Hays RD (1988) Methods for measuring patient satisfaction with specific medical encounters. Med Care 26: 393–402

Zavoral M, Suchanek S, Zavada F, Dusek L, Muzik J, Seifert B, Fric P (2009) Colorectal cancer screening in Europe. World J Gastroenterol 15: 5907–5915

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development of the Dutch Ministry of Health (ZonMW 120720012 and 121010005) and by the Centre for Translational Molecular Medicine (CTMM DeCoDe-project). None of the organisations had access to the data.

Author contributions

ES and TW contributed equally in writing the article. ED and JS obtained funding. ED, JS, EK and MvL carried out study supervision. All the authors provided: study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis/interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Stoop, E., de Wijkerslooth, T., Bossuyt, P. et al. Face-to-face vs telephone pre-colonoscopy consultation in colorectal cancer screening; a randomised trial. Br J Cancer 107, 1051–1058 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.358

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.358

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A digital intake tool to avert outpatient visits in a FIT-based colorectal cancer screening population: study protocol of a multicentre, prospective non-randomized trial - the DIT-trial

BMC Gastroenterology (2024)

-

Face-to-Face Instruction and Personalized Regimens Improve the Quality of Inpatient Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy

Digestive Diseases and Sciences (2022)